Over the last week, a common theme has

randomly emerged out of lectures I have attended and blog posts I’ve read:

scholars and practitioners of conflict (resolution), international affairs,

peacebuilding, and transitional justice are fixated on political violence,

often at the expense of other, more discreet, but equally as menacing forms of

violence.

At a seminar hosted by the Institute for Security Studies in Cape Town, Australian

academic, John

Braithwaite spoke about “cascades of violence” that tend to move and morph

in location and in type. Violence in the

eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo seeps across the

border to Rwanda. Policymakers often

fail to see the impacts of their political decisions and military movements.

One acute example of a violence cascade is the Iraq sectarian war that

was fomented (or mobilized) by the US invasion and occupation of that country.

Not only did the sectarian divide contribute significantly to the more than

100,000 Iraqis that are now dead as a result of the war, but sectarianism is

increasingly problematic throughout the region.

Iran and Saudi Arabia’s feud is starting to resemble US-USSR relations

during the Cold War period, albeit on a much smaller scale. Iran funds Shia,

and non-Sunni, movements and regimes while Saudi Arabia generally supports

Sunnis.

Not only does political violence cascade from

one place to another, but violence can shift and cascade from one type to

another. In South Africa, political

violence has decreased in the last 18 years, since the political transition to

democracy in 1994. However, other types

of violence in South Africa have remained static or have even increased. Violent

crime in South Africa remains quite high.

According to 2010 data, the southern Africa region has the highest rates

of intentional homicide in the world, followed closely by Central America. South Africa, as a country, ranks in the top

10 for intentional homicides per 100,000 people. As of the early 2000s, South Africa had the

highest rape rate per capita in the world.

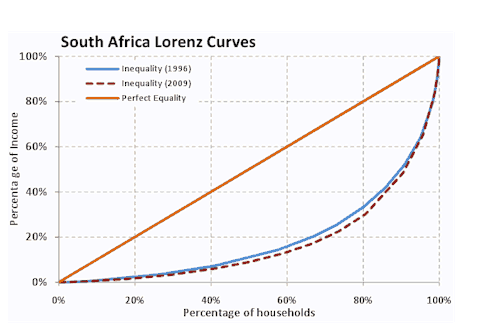

In addition to high rates of violent crime,

South Africa remains one of the most economically unequal societies on the

planet. South Africa has an incredibly

high GINI coefficient, a World Bank statistic that measures the level of

economic inequality in a given country (however, comparing GINI coefficients

between countries is difficult because of the different ways that data is

gathered and because the type of numbers that go into the production of a GINI

coefficient aren’t uniform from country to country). South Africa also ranks

among the top 10 most unequal societies in the world when the average income of

the top 10% is compared with the average income of the bottom 10%, the same

holds when the top 20% is compared with the bottom 20%.

Many community organizations working in

townships and formal/informal settlements in South Africa will also attest to

the disparity of quality service delivery in townships as compared with

wealthier (and usually whiter) areas. Crime,

income inequality, and high rates of HIV (among many other health and education

indicators) attest to acute forms of structural violence in South Africa. Many donors and scholars have turned their

attention away from South Africa, yet continue to refer to it as a prototypical

success story, despite the ongoing economic and social maladies that plague the

country.

In his new, highly-touted book The Better

Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined, Steven Pinker suggests

that violence has decreased over time.

However, Christian Davenport recently pointed

out that Pinker doesn’t look at the full scope of violence.

OK, so maybe the magnitude of violence has been diminished (which Pinker says) but the form may have shifted (which he does not).

Davenport goes on to suggest that governments

aren’t more angelic towards one another, nor to their own citizenry; instead,

the forms of violence have simply changed.

States have also become quite effective at silencing voices of dissent

and weakening movements that attempt to change the status quo and dethrone the

throne-sitters.

Will H. Moore also gets in on the conversation

and suggests

that the fixation of violent political conflict fails to account for structural

violence and the connection between justice and peace. Peace is too often (mis)understood as the

absence of political violence. Within this

(misunderstood) understanding, peace can be at hand when wealth is

disproportionately in the hands of whites while black South Africans don’t have

access to electricity or proper toilets and peace can be manifest while women

have a better chance of being raped than getting an education.

Therein lies South Africa: high rates of

violent crime, income inequality, and a plethora of social structures and

social institutions that prevent the vast majority of South Africans (and a

disproportionate number of non-whites) from meeting their basic needs; yet,

there is a relative absence of overt political violence.

Has political violence in South Africa cascaded

into more severe forms of structural violence? Have social and economic agreements

made during the political transition only entrenched the (unequal) economic and

social status quo while the political landscape changed without benefit for

South Africa’s poor (black) majority?

No comments:

Post a Comment